Dr. Timothy Schilling: A Life in Coffee

Chronicling the impact and legacy of WCR’s founder

As 2020 draws to a close, so too does the professional coffee career of Dr. Timothy Schilling.

A trained scientist with a Ph.D. in plant genetics, Tim began working in coffee in the early 2000s, when he arrived in post-genocide Rwanda to help revitalize the war-torn country through agricultural development. The ensuing projects—PEARL (Partnership to Enhance Agriculture in Rwanda through Linkages) and SPREAD (Sustaining Partnerships to Enhance Rural Enterprise and Agribusiness Development)—helped shape Rwanda into the specialty coffee-producing mainstay it currently is and, more importantly, improve the livelihoods of its smallholder coffee farmers.

Tim roasting coffee in Rwanda in 2008.

Years later, Tim followed his work in Rwanda with another significant project: the founding of World Coffee Research. After realizing how little research existed on the science of coffee quality, he joined with a broad swath of industry collaborators to create the nonprofit, focusing on using agricultural research and development to grow, protect, and enhance supplies of quality coffee while improving the livelihoods of the families that produce it.

To honor Tim’s retirement, World Coffee Research talked to a dozen people who have worked closely with him in his coffee career to tell the story of his work in Rwanda and the creation of World Coffee Research—and their respective impact on the coffee world. What follows are their words, with input from Tim.

Creating Opportunity in Rwanda

Edwin Price, director, Center on Conflict and Development at Texas A&M: Before Tim started working in Rwanda, I had worked with him on a number of projects at Texas A&M, where we were colleagues in the office of International Agriculture. He was a tremendously effective right-hand man for the whole program; he took a number of assignments doing development work in Latin America, Africa, and other places.

We completed an agricultural project in Mali in the late ’90s, and then the Rwanda opportunity came about. PEARL was a joint project with Michigan State University in the lead and Texas A&M supporting, and Tim was the obvious leader that both universities wanted to have based on his prior work. The project would work closely with the agricultural university located in Butare, so Tim moved there with his wife, Michelle, and their young family.

The PEARL project was intended to generate incomes for widows and orphans of the genocide. We knew that we would do this through agriculture, but we didn't know what crop we would focus on.

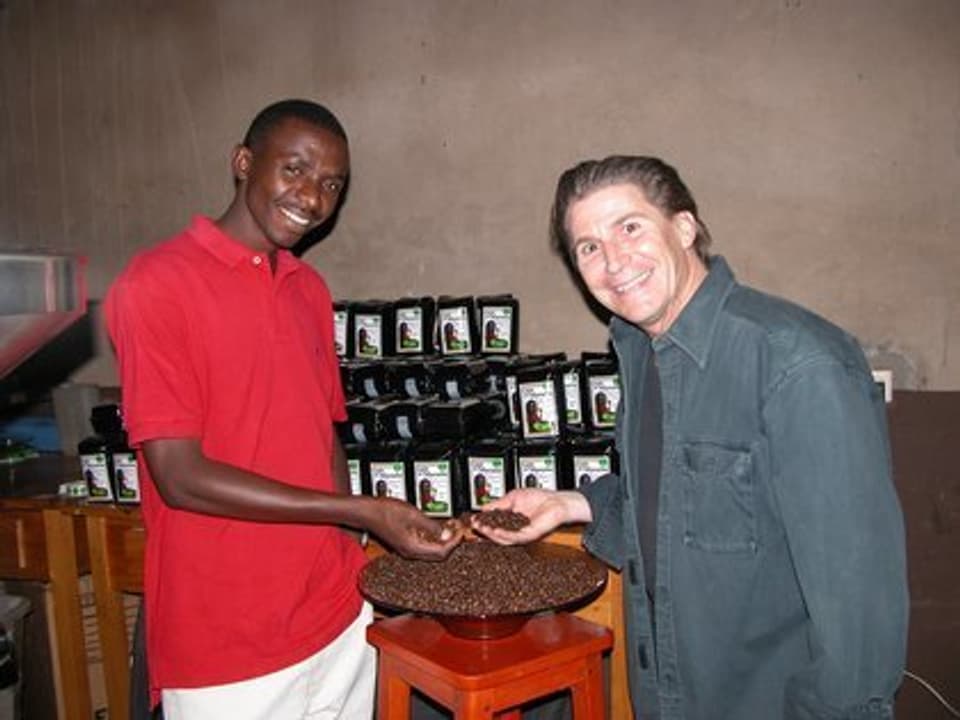

Tim with Jean Bosco Safari at the Maraba cooperative in 2006.

Tim Schilling, project manager of PEARL and SPREAD projects, founder of World Coffee Research: The main element of the PEARL project was to build this outreach center using technology and the research institute’s capacity to identify income-generating activities, and try to make them happen for farmers.

To find what crops to focus on, we did rapid rural appraisals on different agricultural commodities. And when we did those, it was pretty obvious the potential of coffee—you had 450,000 families working in coffee, with a family size around seven to 10 people; it was clear that the biggest impact we could have would be through coffee.

Geoff Watts, co-owner, Intelligentsia Coffee: There was already coffee in Rwanda that had been brought by missionaries long before, but it was a broken industry. I would say it was an industry that was on the verge of extinction because the coffees were being produced without any care for quality. They were all sun-dried natural coffee—nothing washed. But even for the natural coffees, there were few protocols for quality control, so the market for these coffees were large roasters that wanted a source of cheap filler for their blends. Coffee there was trading at a negative differential to the C market, which is already low. So you can imagine that once you got through the lack of transparency and trade, and the low market, and then even lower prices that were paid FOB (free on board), farmers were not making money. It was close to a subsistence scenario.

Lindsey Bolger, former green buyer of Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, second board chair of WCR: In Rwanda, only a hundred coffee trees might be managed by one smallholder, or one small family. So rather than large established estates or even one small finca, it was really a household garden industry with no real structure, no real access to market, and no real intelligence on how to help coffee thrive in Rwanda. As is the case in many places where coffee is produced, Rwandans didn't have a tradition for drinking coffee; it was really just a cash crop.

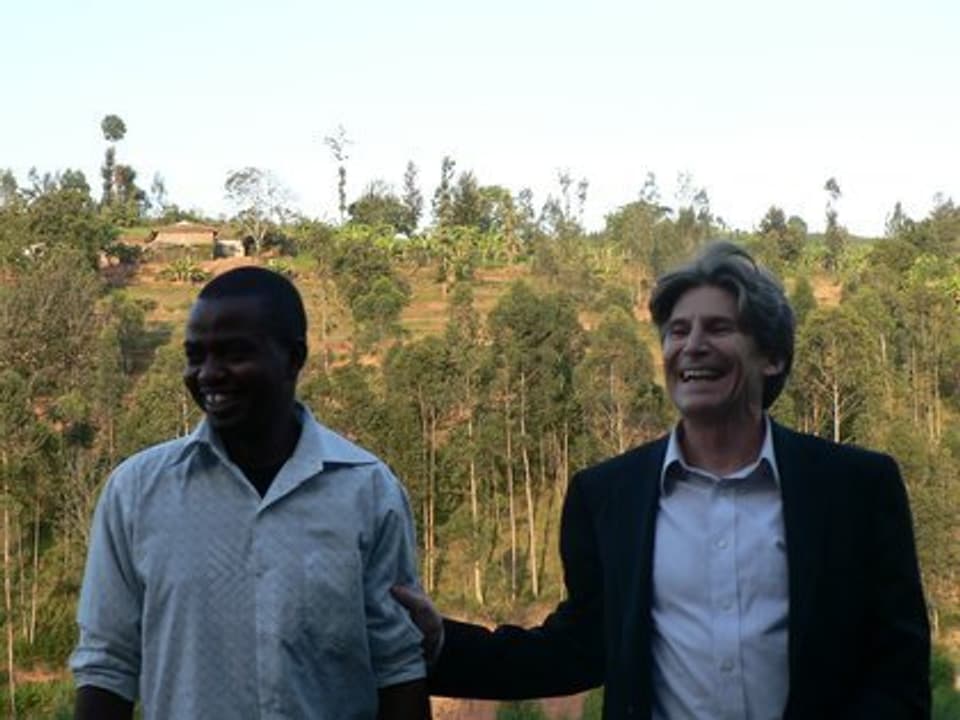

Tim with Lindsey Bolger in Africa.

Watts: Tim saw the potential for quality because he looked around and thought: The raw ingredients are there. There’s coffee, they seem to be good varieties, and there’s altitude. So why doesn’t Rwanda have great specialty coffee? He looked at the other models for washed coffees in places like Kenya and said, "Why can’t we do that here?"

With specialty coffee identified as the focus crop for the PEARL project, Tim and his team of about 30 people—including academic researchers and agronomists—implemented methods for improving coffee quality, such as introducing washed processing, training farmers on best agricultural practices and cupping, and connecting them to global buyers.

Bolger: There was already some expertise there—not only in the network that Tim was working with, but also European NGOs that were on the ground doing their part to reinvigorate this broken and fragmented economy. So the PEARL project was not the only effort, but Tim saw an opportunity to coalesce and organize this coffee economy on a village-by-village scale, and I think that's one of the things that made his approach somewhat unique.

Ric Rhinehart, former president of Groundwork Coffee and former executive director, Specialty Coffee Association: Tim helped to build the first washing station in Maraba [to produce washed-process coffee], and subsequently built washing stations in many villages in Rwanda. Because there were high-quality varieties like Bourbon already growing in Rwanda, once they started washing it and separating it by density and ripeness and whatnot, suddenly it was fantastic coffee.

Bolger: Standing up these washing stations within rural communities was an alternative model to the very centralized coffee receiving and processing model that some of the other NGOs were pursuing. But Tim said, let’s focus on the coffee being grown by these different little population hubs, make sure they're in walking distance to a receiving and washing mill so they can deliver cherries as soon as they're picked, and then really dial in quality.

Watts: It was trial and error in the beginning because he had never built a washing station and was not an expert at coffee. So I think the first iterations had some engineering flaws, and then over time they kept getting better and better.

Price: Once they began to improve the coffee quality, Tim had the insight to start inviting coffee roasters to train the locals on evaluating coffee.

Watts: My first trip to Rwanda was paid for by Coffee Quality Institute; they had a program called Coffee Corps. Once I saw what Tim was doing in Rwanda and the potential for impact, I fell in love with not just the project but with the country and Tim and his colleagues. It’s something I felt compelled to stay engaged with.

Tim, an avid outdoorsman, enjoying exploring Rwanda by bicycle.

Laetitia Mukandahiro, founder, Ikawa House: I was working in Northern Province at Musasa cooperative after finishing high school; I was 19 years old. At Musasa cooperative I was working on the drying tables, and then after two weeks, the PEARL project came there and introduced coffee cupping. They asked if there was someone interested in that project, and I said, “Please give me that chance, I want to learn.” Everyone was surprised because at that time Rwandans only heard about the bad side of coffee—that it wasn’t good for the body. But Tim saw that I was very committed and said, “OK, if you are interested, please come next week to start the training.” Geoff Watts was my first trainer.

Bolger: Tim reached out to me and other roasters for assistance starting a sensory evaluation and training program for the PEARL project. There was the important harvesting and processing work to be done, but after that, there was the work of being able to identify which coffees were exceptional, were worthy of a premium, and could excite buyer interest. And to do that, they needed to train local coffee tasters.

So my first job working for Tim was to propose a protocol for a sensory evaluation panel and methodology. There was an existing protocol that was ideal because it focused on training what we called “naive” tasters—those who may never have had any exposure to what they're evaluating. This process identified candidates who had sensory acuity—not the ability to taste coffee yet, but the raw skills required to be able to differentiate and distinguish between A and B, and B and C.

We identified 25 to 30 candidates through this first wave of screening, and began to train them on flavors commonly displayed in Rwandan coffee. We brought in all the chocolate, nuts, berries, and grains, and spent a good week developing a catalog of terminology. We were laying out the sensory components that we as coffee buyers seek, but that are unknown to folks who have spent their lives in villages in Rwanda or refugee camps in neighboring countries.

Mukandahiro: The training I was in was about six weeks; at the end I passed the exam, and I felt like the champion of the world. A smallholder specialty coffee association in Rwanda called RWASHOSCCO recruited me immediately to be the lead in quality control. And from there, my coffee career took off.

Watts: For the next four years I went to Rwanda each year for several weeks at a time to do cupper trainings within the PEARL project. One of the genius elements of Tim's plan was he not only invited people that he thought could contribute ideas or feedback, but people who were in a position to bring the story of what was happening there back to their markets, and who could be good ambassadors for the coffees.

Peter Giuliano, chief research officer of Specialty Coffee Association and former green buyer of Counter Culture Coffee: Tim instinctively was building this vision for a specialty coffee sector for Rwanda by saying: Let’s talk to the people who actually do specialty coffee. It wasn’t long before he invited me to come to Rwanda. The original idea was to train coffee cuppers, which was an unusual thing for a development program to focus on. But I was happy to go and join him.

Tim delivering a presentation at exporting company Rwacof in Rwanda.

Bolger: I want to say that Community Coffee in Louisiana was the first U.S. buyer of coffee from the PEARL project. We started buying it a bit later at Green Mountain; it was one of the first special reserve coffees that we were able to feature, which was the perfect slot for them because they were unique and limited. We could roast them and make sure they were sold fresh, and tell the story of the coffee in a more descriptive and deep way.

Watts: Intelligentsia started buying the coffees early on, and Rwanda became the largest source of African coffee for us pretty quickly.

Price: The PEARL project continued for about five years. At the end of 2005, we launched another five-year project called SPREAD. Texas A&M became the lead of the project with Michigan State in a supporting role, and we continued the specialty coffee initiative that was becoming successful.

Schilling: By the end of the PEARL project, it was clear that we had put coffee on the Rwandan agricultural map. We had trained so many people under PEARL that we now had very strong individuals with a lot of technical acumen to work in the SPREAD project. So SPREAD was all about “spreading” this project around Rwanda. At the end of PEARL we had only put into place seven or so washing stations at different cooperatives. But with SPREAD, it became hundreds of washing stations.

Watts: Over the course of the next years, the washing stations just started to multiply like Gremlins.

David Rubanzangabo, founder, Huye Mountain Coffee: For PEARL, I was the technician in charge of training cooperatives on coffee quality improvements, and the organizer of cooperative members. For SPREAD, I was the supervisor of 86 new coffee washing stations built in the country. My job was coffee quality control among those 86 washing stations. Tim was my director and advisor to link the market needs with the coffee produced.

Bolger: Tim and the trainers helped build the local expertise to the point where they had not only developed enough professional capacity among cuppers, but also capacity to ensure that things like chain of custody and proper labeling and segregation of various lots could meet the standards for the Cup of Excellence. Developing these local experts was a big reason they were able to host Cup of Excellence Rwanda—the first one in Africa—in 2008. I was a judge for the first COE trial in Rwanda, the Golden Cup, and then eventually for COE in Rwanda.

Mukandahiro: During the SPREAD project we had the huge honor of hosting Cup of Excellence. I was selected as a member of the national jury, and since then I have been on the Cup of Excellence international jury four times.

Schilling: It had been a goal of ours to bring Cup of Excellence to Rwanda—because we knew it would ring bells all over the coffee world, and highlight Rwanda as a specialty origin. It’s amazing the effort that goes into putting on a COE event, especially in a new country and especially on a new continent. But it was a success; it really did a lot for Rwanda, no question. And Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda, was there as well. It was amazing.

Rhinehart: The impact of the PEARL and SPREAD projects was undeniable. In 2010, just after the SPREAD project ended, there was virtually no natural coffee in Rwanda; all of it was washed arabica. And virtually all of it was specialty coffee quality. And Tim did that—with the help of a lot of collaborators.

Tim at the Maraba cooperative in 2009 with his friend Pascal Gakwaya Kalisa during a celebration for Tim's departure from Rwanda.

And that work changed the livelihoods of a few hundred thousand Rwanda farmers in amazingly profound ways at a moment of time that was as dark as you can imagine. This was after the genocide, and the life of a rural Rwandan was forever colored by the genocide. The PEARL project created jobs, hope, pride, and an opportunity for people to work together. It is a lasting impact that will persist for generations.

Bolger: It's such a tremendous success story to see the folks that worked with Tim in those early days of the PEARL and the SPREAD projects are really the coffee professionals who are leading the industry in Rwanda today.

Watts: When I look at the work Tim did in Rwanda and the blueprint he engineered, I see echoes of it all around the world today. Elements of his approach are being taken as the core elements in any development work that's being done in coffee. He not only was able to directly change the trajectory of an entire industry and a country, but he was able to build a protocol that is continuing to help development work around the world.

Uniting the industry for coffee’s future

Rhinehart: In 2009, I was at the Specialty Coffee Association of Europe conference in Cologne, Germany. Tim called me and said, “I got an idea I want to talk to you about.” He drove to Germany from France and met me in a hotel ballroom. And he gave me this pitch on starting the Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative—which would later become World Coffee Research.

He had done some experiments around quality and its relationship to post-harvest processing, and was astounded at how little scientific research there was on coffee quality. So he got the idea to create this initiative, and he asked me if I would support it officially from the SCAA side. I told him I would personally take it to the board and be 100% supportive, because I’m a believer that scientific research supporting the industry’s longevity is and was fundamental to what the industry needs, and fundamental to the mission of the SCAA.

Doug Welsh, VP coffee & roastmaster of Peet’s, incoming WCR board chair: Ric was so key; he was really I think Tim’s original thought partner. There’s no question that this was sprung out of the mind of Tim Schilling, but I think it wouldn't have been realized without someone or an organization to bring it into being. Ric was really instrumental, as were other key

Rhinehart: We started a dialogue where he was creating drafts to frame what the initiative would be, and I would add and respond, until we got to something we thought was ready for primetime. We presented it to the SCAA board, and they were willing to put their weight behind it. In 2010, the board authorized me as the executive director to spend up to 30% of my time working on that initiative. At the same, Tim had sold the initiative to his boss, Ed Price, at Texas A&M. Ed agreed to let him work essentially full-time on developing the Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative.

Tim evaluates Catuai plants with Benoit Bertrand from agricultural R&D organization CIRAD.

Watts: We referred to it in shorthand as GCQRI, and from there it was affectionately known as “Geekery.”

Giuliano: It was around this time that we were planning the first Re:co. I asked Tim if he would present his coffee quality research at Re:co, which was then called the SCAA Symposium. He agreed, and he did. One of the interesting things about that research is there was too much noise in the cupping data for it to really tell us anything. But Tim stood up there in front of everybody, and he delivered that almost non-result with so much passion and interest that he got the room excited about coffee research, and about this new Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative.

Patrick Criteser, president & CEO of Tillamook, former president & CEO of Coffee Bean International, and first board chair of WCR: I saw Tim speak about the research he was doing, and he mentioned the need for the industry to come together in a pre-competitive way for scientific research. So I waited in line at the end of his talk and went up and said, “Hey, why isn’t the industry doing this more?” And he said, “Well yeah, I think we should be.” And it just went from there.

In the following months, several “genesis donors” wrote checks to bring the Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative to life. These initial contributions included $35,000 from Coffee Bean International, $40,000 from Green Mountain Coffee, $25,000 from Peet’s Coffee, and $10,000 each from Intelligentsia Coffee and Counter Culture Coffee.

Bolger: Before there was a “thing,” there needed to be resources to explore the thing, so that's what Green Mountain Coffee and the other genesis donors did. I helped Tim make the business case to Green Mountain for why an organization like the Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative was an essential investment for companies like ours, and why it was so important to have a research and development conduit for the coffee industry.

Rhinehart: This early work culminated in October 2010, when we held a congress at Texas A&M bringing the industry together. I convinced Tim that neither of us had the organizational chops to pull off what was effectively a conference, so we hired Shauna Alexander Mohr to plan and organize the meeting. We sent out invitations and brought the industry to Texas A&M.

Price: I think we had about 60 to 70 coffee industry people from all over the world. Over two days’ time we went through a process where everybody expressed their aspirations and asked what we could do as an industry.

Tim during a trip to South Sudan in search of wild arabica in 2012.

There was one other event during that meeting. We were meeting at one of the office towers here on campus. It was around 4:30; we were almost ready to break for the day. Then we had a lockdown because of a suspected gunman on campus.

Giuliano: It turned out to just be a guy carrying his wooden ROTC rifle in the wrong way on the wrong bus or whatever. But there was a good hour and a half there where we were all locked in and I’m thinking, oh my god, this has gotten scary.

Rhinehart: Tim and Shauna and the volunteers did a remarkable job of pulling that congress together, and at the end of it the Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative was born, and we started life as the Geekery. I was the official incorporator of it; we incorporated in California as a 501(c)(5). We chose a 501(c)(5) very intentionally because one of the requirements was that we had to work to the benefit of farmers, not of roasters or consumers. And it has been critical to keep that as our legal framework—among other things, it has kept us very focused on who our work ultimately serves.

With GCQRI incorporated, Tim spent a great deal of time recruiting coffee-industry companies to support the new organization.

Jim Trout, vice president, research & development - coffee, J. M. Smucker Company: I met Tim in 2012, when he and Ed Price came to the J.M. Smucker headquarters in Orrville, Ohio, to introduce the concept of World Coffee Research to us—they had recently adopted that name. Because J.M. Smucker owns the Folgers brand and other big coffee brands, we’re a significant player in the U.S. coffee market. I think having us as part of the WCR family was important to them to achieve some scale and to recruit other companies.

So they came to visit us, and it was an amazing experience, to be honest with you. I just remember the compelling call to action that Tim gave us—since it was pre-competitive, we’d all be working together for something that benefited the industry as a whole. But the biggest thing that Tim brought was this notion that coffee was an orphan crop and it was under threat. If we didn’t do something about it, it was going to be impacted by climate change and disease, and everything would be threatened—supply, quality, farmers’ livelihoods. And the call to action was just so clear. We were moved by it as a company, and of course we wound up becoming one of the earliest members of WCR.

Tim shows affection for the original Gesha accession from the CATIE collection in 2015.

Criteser: As the first board chair of WCR, I spent a lot of time with Tim flying around and visiting folks to get them to commit to the program. Tim’s vision and his credibility just drew people into the idea—he could make things happen, with this contagious energy for the topic. And WCR just started to take off. It was really exciting.

Rhinehart: One of the things that happened was in 2012-13, roya hit Central America really, really hard. Rust was “good” for WCR the way that famine was “good” for UNICEF. It just drew all the eyes onto the problem and restated it.

We had approached the problem as being: We don't know anything about arabica coffee, we don’t know anything about quality drivers. We're building this global specialty coffee industry with a lack of knowledge, and there are tremendous risks we don’t know about. And the supply is constrained, and becoming more constrained by climate change. That’s a pretty esoteric foundation to build a pitch from.

Then rust hit, and you could see the impact. So suddenly we could get appointments and get checks written that we couldn’t get prior to that. And Tim was moving like a house on fire. He grew the business from zero to something really substantial, just on sheer guts and willpower. It was just a pleasure to watch.

In the mid-2010s, World Coffee Research embarked on the project of securing a research farm where it could execute on-farm trials to help ensure the long-term profitability of smallholder coffee farmers.

Schilling: If you're an agricultural research organization, you need to have a research facility to test different things, so an experimental farm is necessary. I gave a seminar at Texas A&M, and afterward this guy Guayo came up to me; he’s a member of the Aggie Network (a Texas A&M alumni group), and he said, “What can I do?” And I said, “If you could give us a farm, that would be really nice” (laughs).

Eduardo “Guayo” Palomo, El Salvador coffee farmer: At first I said I would donate part of my coffee plantation. My feeling was: We cannot let this opportunity go by. Our industry needs to partner with research institutions—I think it’s the only way that our livelihood, our culture, and this crop we love so much is going to sustain into the future. I spoke to my friends, and we started looking at other options. We were able to secure a 90-year lease for WCR to use to conduct research.

Tim with Guayo Palomo during a visit to the WCR experimental farm.

Schilling: What they were proposing was extraordinary—you’ve got a farm, a team of agronomists, a cupping laboratory, a processing center, a mini washing station … man, you can do everything you need to do in coffee there. I said, “This is perfect!”

In 2018, Tim announced his plans to retire from World Coffee Research in 2020, and the board—which includes Tim—was tasked with finding his successor.

Schilling: 2017 and 2018 were huge years for WCR. We went from a staff of seven or eight in 2016, to like 20 and then 35. That kind of growth, which is apparently normal for a successful NGO, requires a different skill set. My passion was never in process. My passion was always getting stuff off the ground. So we knew that the new CEO had to have a similar skill set to mine in terms of knowledge of agriculture, but they also had to be more oriented around organizational development. We were so fortunate to find Vern—she’s the real deal.

Jennifer “Vern” Long, CEO, World Coffee Research: The first time I met Tim, he was sitting at a conference table accompanied by the board for my first interview in the process. And his enthusiasm shown out like a star radiating. He just created a warmth and a love about the organization.

Welsh: The greatest tribute I think we could accord Tim is we had this huge challenge to try to find his replacement. Of course we wanted to clone him, but we didn't have the technology (laughs). But I think we, largely with Tim's help, found someone who will take Tim's vision to the next level.

Long: When I took over as CEO, he served as a senior advisor to help orient me to the coffee community. He served as an interlocutor with the trade and with roasters to help us understand each other. Tim created a very smooth and efficient handoff, and engaged me from the beginning in sharing his wealth of knowledge and relationships to accelerate my progress.

Welsh: Maybe the key is that Vern and Tim are ethically aligned. They're both tremendously capable people with phenomenal capacity, but really in the back of their minds they're always thinking about the small farmer. What would the tools and technologies be that could be scaled up so they could improve the livelihood of a small-scale farm household? That's what motivates them; that’s what they both want to achieve.

Though Tim retires from WCR in December 2020, he will continue to work on projects related to coffee, and his legacy in the coffee industry will live on.

Tim with Vern Long, his successor as WCR CEO, during a trip to El Salvador in 2019.

Rhinehart: Tim is the most amazing intersection of an entrepreneurial spirit, a research scientist, and a charismatic leader. He brought all those things together with World Coffee Research in the most magical way to create a lasting institution. He had people like me and others trying to raise more money and promoting for him. But Tim did the work; he made it happen.

Schilling: I can’t even see retiring. I don't feel like I'm old or anything. But I want to first just do nothing, at least for six months to a year. I want to turn myself off a little bit and detach as much as possible. But obviously I can’t detach from coffee. I think the most significant thing I could deliver in these last years is trying to get younger scientists involved in coffee research. So I’ll be looking at that.

Giuliano: I wrote a blog post a couple years ago titled “Plant Breeders Are Heroes.” I didn't realize that plant breeders were heroes until Tim showed me that. It takes somebody like him to make plant breeding—which may seem mundane to people— exciting. Very few people, particularly on the scientific side, can be that bridge. He can be in a room full of scientists having an academic conversation, then he can change gears and be just as entrepreneurial as any coffee company owner. There are vanishingly few people who can do that; I aspire to do that. I feel like he blazed a trail that people like me can follow; I hope people know that.