Multiclass Classification of Agro-Ecological Zones for Arabica Coffee

A study published in the journal PLOS ONE confirms predictions that half of the land currently suitable for Arabica coffee production will no longer be suitable by 2050. But it also identifies the key climate zones in which coffee flourishes, and shows how these zones will change by 2050, which brings new insights about what can be done to adapt. The full study is available at PLOS ONE.

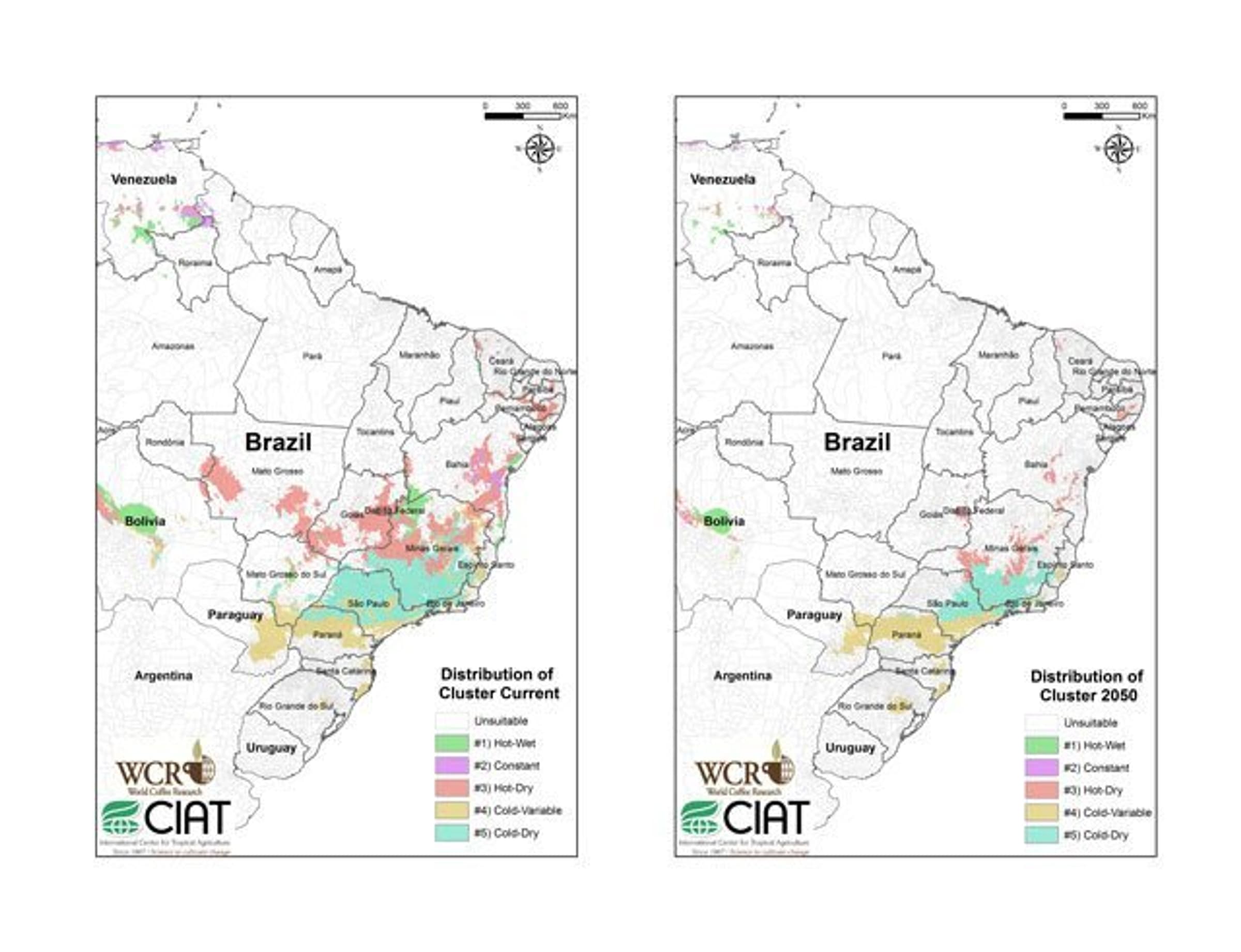

Not all coffee climates will be affected equally by climate change. The new research shows for the first time how each of five “agro-ecological zones” for coffee will respond to climate change by the middle of the century. The findings show the biggest losers will be producers in hotter areas with long dry seasons, such as parts of Brazil, India, and Central America. There, almost 80% of current coffee areas will become unsuitable.

Key findings summary

- Confirms predictions of 50% reduction in land area suitable for Arabica coffee production by 2050

- Dramatically expands our understanding of what it means for land to be “suitable” for coffee production now and in the future

- Gives a detailed picture of which types of coffee climate will be most affected by 2050, with significant losses predicted for Brazil, the world’s largest coffee producer.

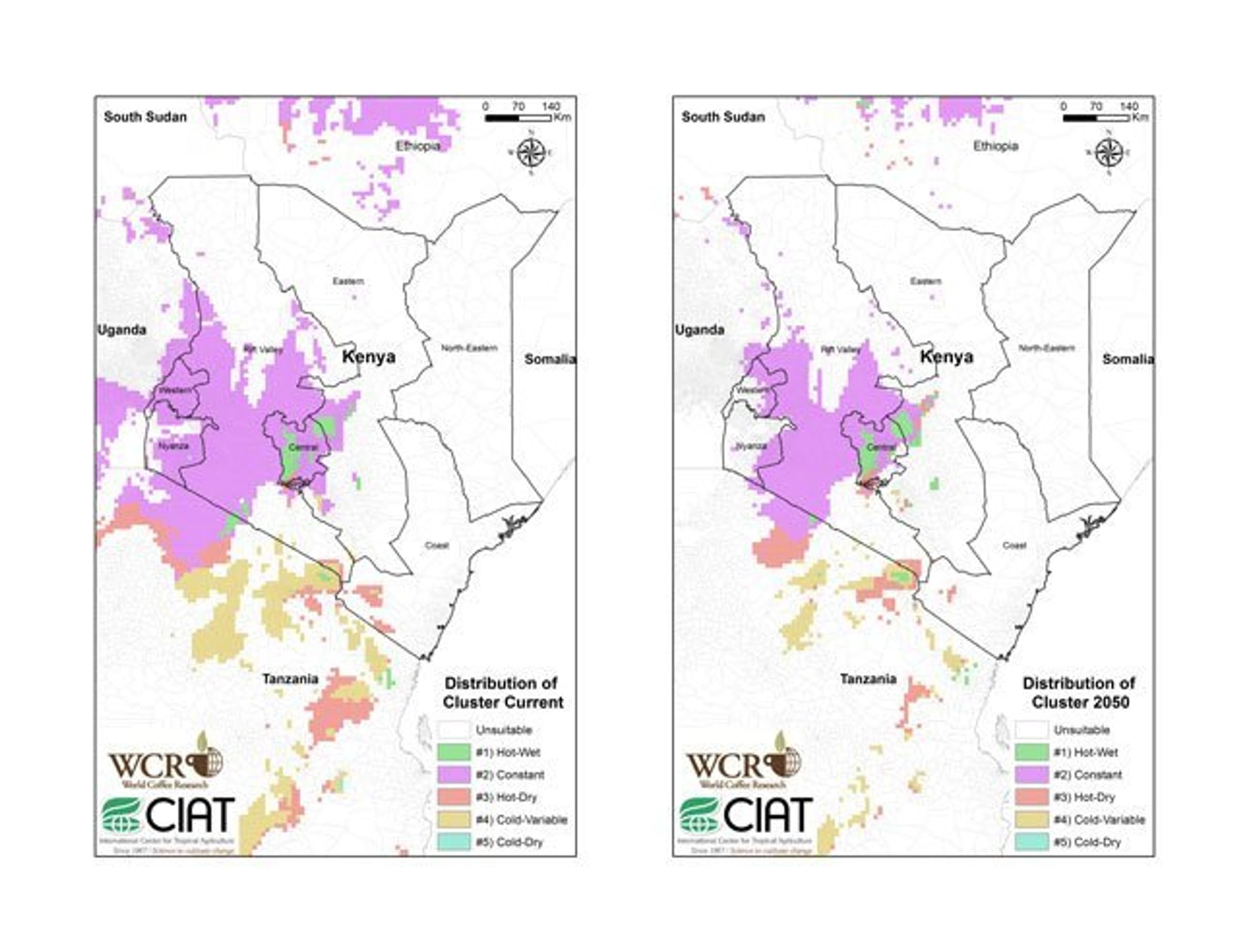

Areas around the equator with cooler and seasonally constant temperatures, including many parts of Colombia, Ethiopia, Kenya and Indonesia, will be least affected by climate change—good news for the specialty coffee industry, which relies on these regions for its highest quality coffees. But even those areas are expected to suffer a one-third slump in suitability by 2050.

The highest losses will be in hot, dry regions such as northern Minas Gerais state in Brazil, parts of India, and Nicaragua—areas that currently give some of the highest yields of Arabica coffee. Nearly 80% of the land in this climate zone will become unsuitable for coffee by 2050.

Areas with relatively constant temperatures, such as much of the coffee land in Kenya (represented in purple), are predicted to remain more effective for coffee growing in the coming decades.

The study predicts that nearly all of the coffee area in Brazil's hot-dry areas (shown in pink) will become unsuitable for coffee production by 2050.

“Overall, the Arabica market is extremely threatened,” says Christian Bunn, the study’s lead author, a researcher for the Colombia-based International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). “There is rising demand. In the future, we’d need more area to grow coffee on, but we’re going to have less."