The coming climate

What are the right varieties for tomorrow?

An IMLVT site in Zambia. The site is in a hot/dry location, which allows researchers to observe how coffee varieties perform in a climate that is similar to the hotter/drier climates expected for many coffee regions in the coming decades.

Which coffee varieties are deeply affected by small changes in climate—for example, hotter, drier temperatures—and which have stable performance across a wide range of climates? How does climate impact yields, disease tolerance, or cup quality? Somewhat shockingly, we simply don't know—despite accelerating impacts of climate change and the incredible economic importance of the $100B global coffee industry.

Plants that go in the ground today will still be growing on farms 20 years from now—but many coffee-producing regions are predicted to become much hotter and drier over that time period. The varieties that do well today in hot, dry conditions will be good bets for farmers who live in areas predicted to become more hot and dry over the coming decades.

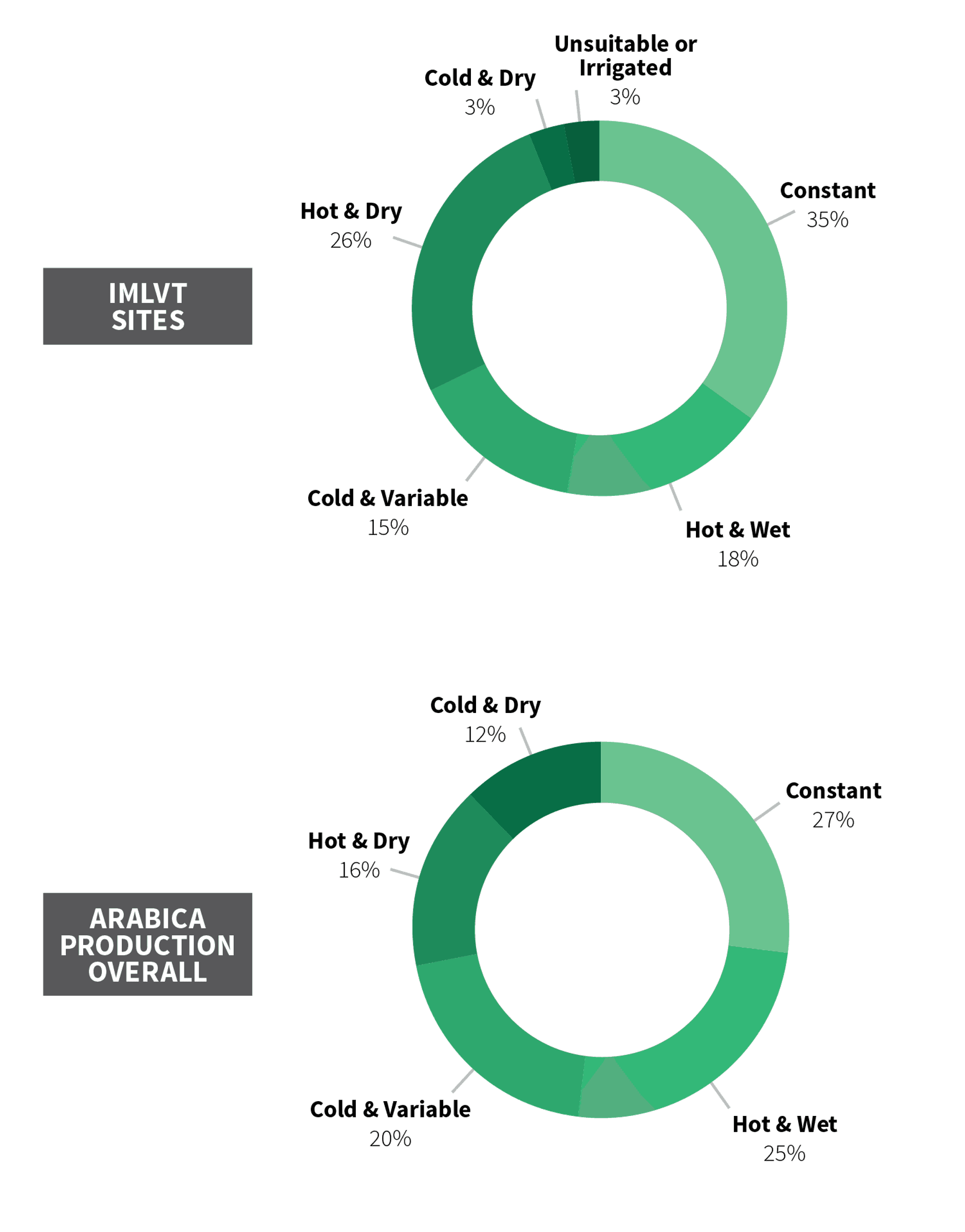

The International Multilocation Variety Trial is the first global study to assess how key coffee varieties respond to different climate conditions. IMLVT sites around the world have been carefully sited in a diverse set of environments that represent the five “suitable climate zones” for Arabica coffee (described by Bunn et al., 2015):

- Constant

- Hot and Wet

- Cold and Variable

- Hot and Dry

- Cold and Dry

For example, currently 25% of IMLVT sites are located in hot, dry zones (see figure below), allowing us to see how hot/dry climates impact the flavor and quality of varieties.

But one trial site, in Zambia (hosted by our partners at OLAM) is situated in an extreme environment that is so hot and dry it is considered unsuitable for non-irrigated coffee production.

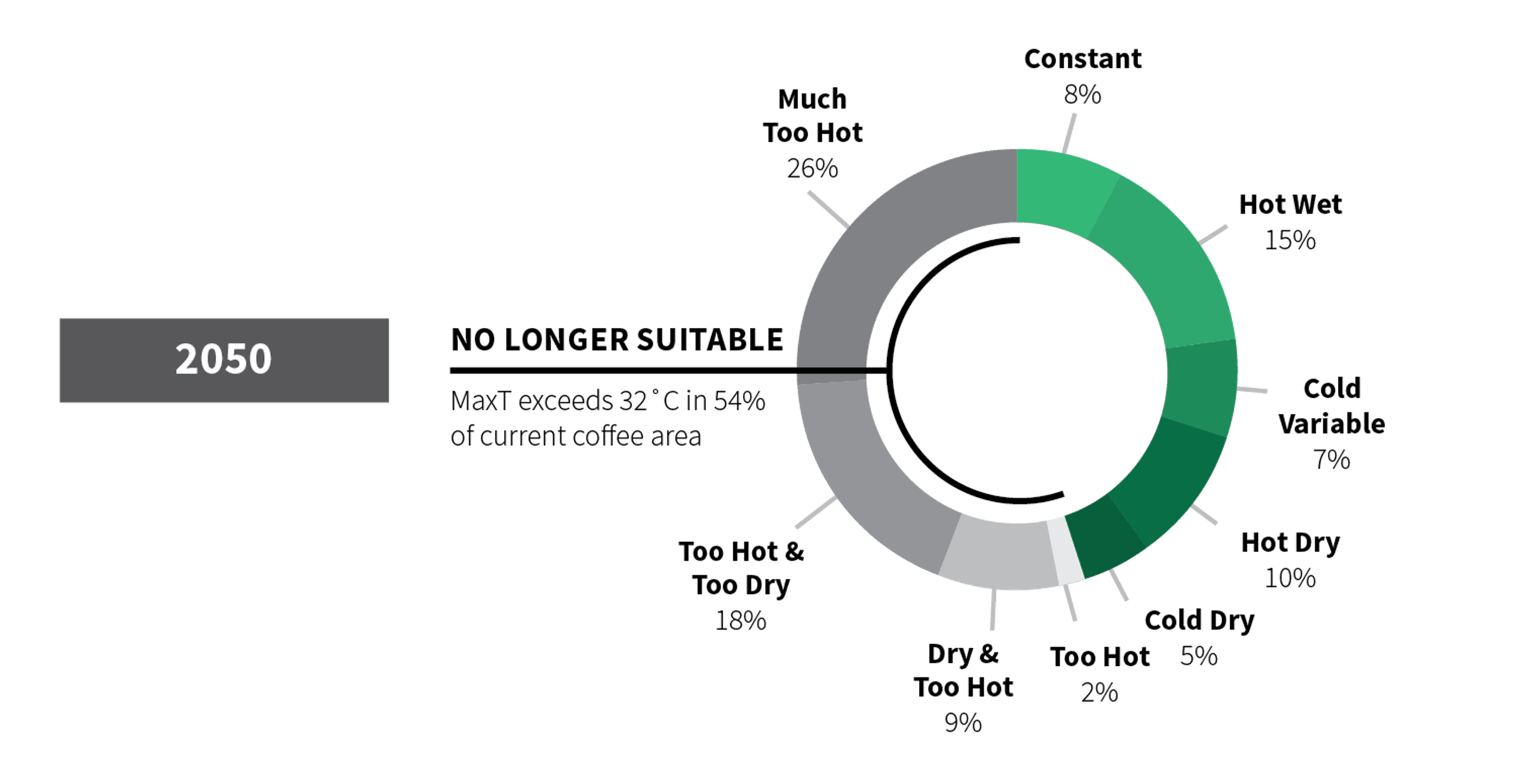

Crucially, while about 16% of coffee production today occurs in zones that are hot and dry (but still suitable), by 2050 nearly all of that land will have become so hot and dry that it will no longer be suitable for coffee production. Overall, 46–49% of land suitable today will become unsuitable by 2050.

By studying which varieties perform well in areas that are today as hot and dry as we expect many coffee productions zones to become by 2050, we will learn not only which current varieties are "best bets" for replanting in the near term, but also will be able to investigate the mechanisms that allow some varieties to perform better than others—which, in turn, will fuel breeding efforts to create more resilient varieties for tomorrow.

An approximately two-year-old Geisha plant in Zambia—not doing so bad!