When it comes to coffee leaf rust, is shade good or bad for coffee?

The answer comes from a deep dive into the microscopic world

Researchers and students from CIRAD and CATIE, with funding from World Coffee Research, spent nearly a year taking exhaustive measurements of the movement of rust spores in a coffee agroforestry research site at CATIE in Turrialba, Costa Rica. Their findings were published in Crop Protection.

Researchers have known for years that shade can have both positive and negative effects on coffee leaf rust—but this team wanted to understand what was behind some of those different impacts, so that better guidance can be provided to coffee farmers interested in agroforestry—an increasingly important approach for managing rising temperatures in many coffee regions.

It turns out to have a lot to do with rain. The researchers looked at how dense shade (of the casha tree, Chloroleucon eurycyclum) impacted the way raindrops gathered, fell, and splashed—taking coffee rust spores along for the ride. The upshot? Dense shade trees like Chloroleucon eurycyclum are problematic when it comes to coffee leaf rust.

Rust lesions on a leaf. Photo credit: Jacques Avelino

To understand why, it’s important to know a little bit about how rust works. Leaf rust is a fungus whose single-celled spores are dispersed primarily by wind and water. When a spore encounters a susceptible coffee leaf in the presence of water, it can germinate and infect the plant tissues, rapidly colonizing the leaf (a single lesion can produce 400,000-2,000,000 new spores!). Those new spores are then carried by wind and rain to other leaves nearby; if conditions are right, the infection can rapidly spread through a coffee farm, causing serious damage. On the other hand, spores that don’t quickly find a home on a new leaf will die. Even though water is necessary for rust’s life cycle, the researchers discovered that rainfall actually helps control rust, by washing rust spores off of coffee tree leaves and onto the ground, where they die.

It turns out this is one of the biggest problems of dense shade. Dense shade reduces the amount of rain reaching coffee tree leaves, minimizing the “washing” effect of rain. The researchers found that there were 1.62 times more rust spores washed out of trees in full sun than under shade. Dense shade also increased the kinetic energy and size of raindrops, which heavily impacted leaves and contributed to release and dispersal of rust spores. Overall, the number of spores produced and preserved on coffee leaves under shade was more than double the average amount per leaf under full sun (2.22 times more).

Wash-out effect critical

The “washing” effect of rain had never been reported before, and the paper’s authors suggest it may have contributed to the coffee leaf rust epidemic that ravaged Central America starting in 2012. The authors estimate that as many as 25% of spores may be washed off of coffee trees by rain in full sun, vs. only 8% below shade. In the second half of 2012, there was lower-than-average rainfall (at a time in the crop cycle when coffee leaf rust incidence usually increases); this lower rainfall may have contributed to reduced “washing” of coffee leaves in agroforestry environments, contributing to its rapid spread through the region.

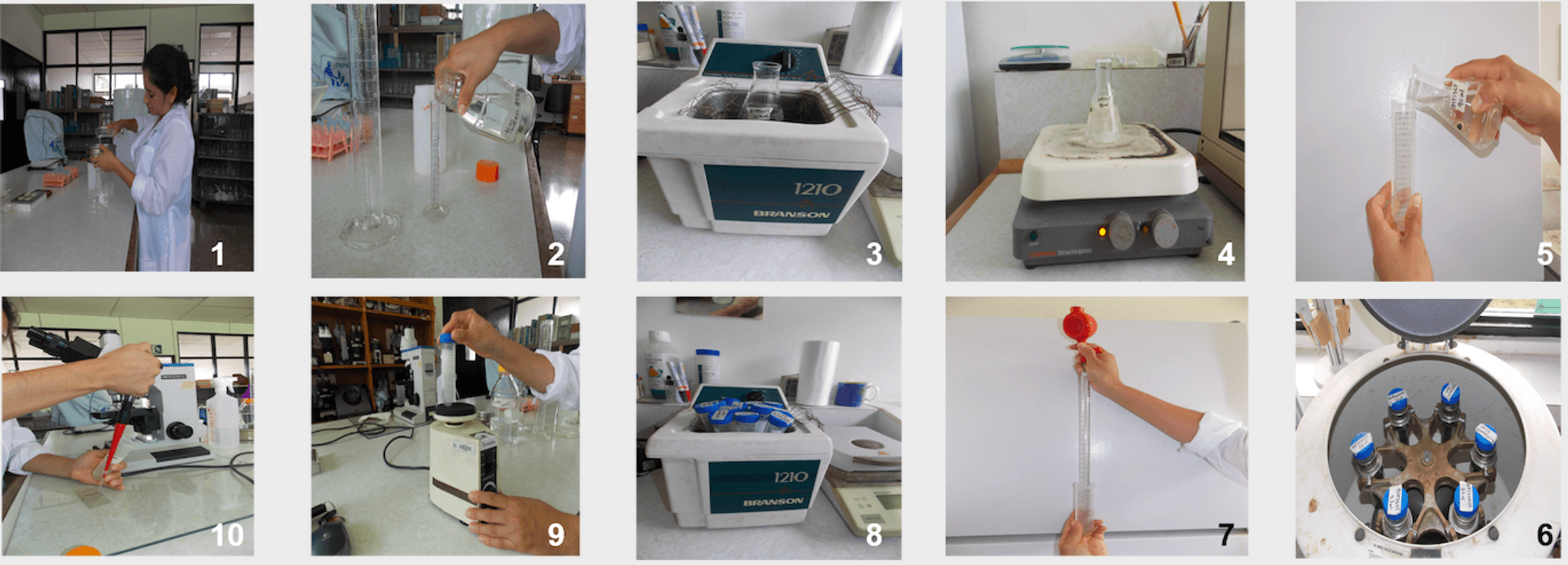

The system of containers that allowed the researchers to measure how rainfall impacted the movement of microscopic rust spores.

Splash cups and varnish: Measuring the movement of microscopic rust

The researchers from CATIE used fascinating methods to come to these conclusions, comparing and measuring how rainfall impacted the movement of microscopic rust spores under shade and full sun. They counted individual spores on infected leaves, placed containers underneath the trees to measure how many spores were washed off by rain, and used a sticky varnish to capture rust spores deposited on otherwise healthy-looking leaves. They also measured the kinetic energy of raindrops using splashcups. All in all, the research team took hundreds of measurements in the field and in the lab. The collected spores were processed in the lab and painstakingly counted using microscopes.

Marta Beatriz Segura processed samples from containers for uredospore counts in the lab

Shade’s other effects

Shade trees in agroforestry systems can help control coffee diseases in many ways, for example by providing refuge to birds, ants, spiders and fungi that help control pests and diseases. Shade trees also modify microclimates and can impact the overall health of coffee plants, providing protection from infestations. Shade trees have been reported to help manage several coffee diseases. But others are made worse by shade (see box below), probably because humid conditions in the understory favor these disease developments. But some shade trees are also alternate hosts for M. citricolor, C. koleroga and C. salmonicolor. But in many other cases, the effects can be mixed – sometimes shade helping the disease, and sometimes hindering it – probably because shade affects pest and disease development in opposite directions, and that, in addition, may interact with the environment.

Implications for managing shade on coffee farms

The paper’s authors point out a challenge in their findings: “Shade trees are essential for adapting to increasing temperatures, but shade trees have unwanted effects on coffee leaf rust.”

But the detailed findings of this study point to shade tree qualities that can reduce these negative impacts. The authors suggest farmers consider the following in coffee agroforestry:

Small, pinnate, flexible leaves and low leaf-area index that will reduce rainwater interception and accumulation on the canopy, or small trees that will reduce the height of fall of raindrops, and therefore their kinetic energy. Pruning of shade trees during the rainy season will open the canopy and increase throughfall.

Students at the front

Two students completed their master’s theses in conjunction with the research described in the Crop Protection article. Both Marvin Alejandro Brenes Loaiza and Marta Beatriz Segura Escobar received master of science degrees from the Agroforestry and Sustainable Agriculture program at CATIE in 2017. The students were led by Jacques Avelino, a world-renowned expert on coffee leaf rust based at the French research institute CIRAD, and Elias de M. Virginio Filho, an agroforestry researcher who leads collaborative research programs at CATIE.

To read the full study, visit Crop Protection.