Harnessing the power of natural enemies to fight coffee leaf rust

We catch up with a research project delving into how coffee leaf rust’s natural enemies can be harnessed to fight the disease causing severe challenges for coffee production worldwide.

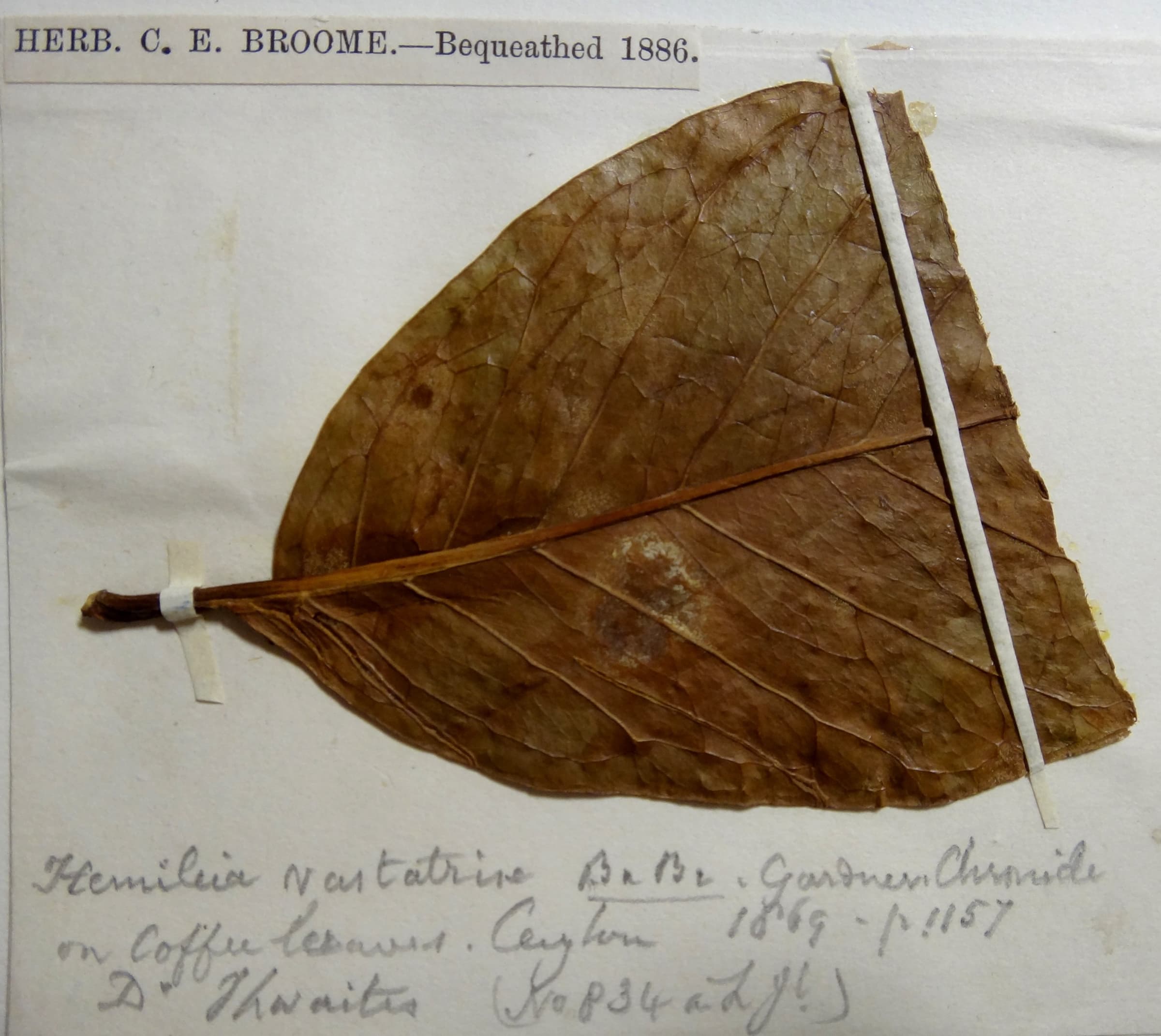

Historical herbarium sample deposited in the Botanic Gardens of Kew (England). Coffee leaves attacked by coffee leaf rust collected in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) which served as basis for the description and naming of the fungus as Hemileia vastatrix. Starting in 2015, researchers from Brazil, UK and Africa, engaged in WCR project, surveyed the native habitats of coffee in Kenya, Cameroon and Ethiopia to search for microbial life that helps coffee trees fight against rust

Dr. Robert Weingart Barreto is no stranger to Africa’s wild coffee forests. A professor at the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) in Brazil, he is the lead researcher of a World Coffee Research project that seeks to use biological control (also known as biocontrol) to combat coffee leaf rust, the worst disease in coffee farms around the world. Dr. Barreto and his team of researchers, in cooperation with the British plant pathologist Harry Evans (CABI) and African scientists, have ventured into wild coffee forests in Ethiopia, Kenya, Cameroon, and beyond, in search of natural enemies that coexist with the rust in its natural environment. They hope that some of them might offer new tools in the fight against the rust.

Robert Barreto driving towards a coffee forest in January 2015.

Into the woods

Organizing a collecting mission to a wild coffee forest is no easy task. These forests are located remotely and journeying to and from such isolated areas involves risks and logistical difficulties. Along the way, Dr. Barreto and his team have visited sites that most coffee professionals will never glimpse. “We’ve seen coffee plants in the forest that are over a hundred years old,” he says. The team collects leaves, berries and twig samples from wild and semi-wild coffee plants and preserves them for later analysis in the search for natural enemies of the coffee leaf rust.

Specifically, Dr. Barreto and his team are searching for fungal natural enemies that are either ‘mycoparasitic’ on the rust – meaning they will attack and consume it – or ‘endophytic' growing within the coffee plant – and, potentially, acting as bodyguards protecting the plant from rust infection. The idea behind this approach, known as ‘classical biological control’ (CBC), is to reunite the rust with its co-evolved natural enemies which were left behind in its native African centre of origin. CBC can be an effective, sustainable and ecologically benign method of fighting plant disease, as well as being highly cost effective.

Harry Evans and local guide collecting samples of mycoparasties found together with coffee leaf rust in wild coffee forests in Kakamega forest, western Kenya.

Dr. Barreto says: “We are finding fungi that we’ve never seen before, and that no one knew were capable of growing inside living plants.” However, these endophytes only come to light following a laborious isolation protocol from the healthy coffee tissues, which needs to be done in situ, in Africa. It should be stressed that these surveys could not be undertaken without local collaborators, who also ensure that permits are in place both to collect the material and to evaluate their potential.

During this research project, the UFV team has collected a total of 1,392 endophytes and mycoparasites. From these, the team is now selecting 10 to 20 candidates for more comprehensive screening in the laboratory and greenhouse, the most promising of which will be tested in the field.

Success in cacao

The classical biological control strategy for management of plant diseases isn’t new for agriculture, although it is still a relatively novel approach for coffee. Dr. Barreto points to cacao, a crop with much in common with coffee that has seen success using CBC. In Brazil’s Bahia state, witches’ broom disease has wreaked havoc amongst cacao growers. It turned Brazil, the second largest cocoa producer in the world, into a net importer of the product. But the introduction of a mycoparasitic fungus called Trichoderma stromaticum, a natural enemy of witches’ broom from the Amazonian centre of origin of the cacao plant, has made a valuable contribution to the management of this devastating disease. The deliberate introduction of any new species into an environment requires caution and Dr. Barreto describes the common argument against biocontrol as: “It’s a dangerous thing to import natural enemies; it could go wrong and cause economic damage and ecological catastrophe.” Nevertheless, for decades the introduction of fungal natural enemies to control environmental and agricultural pests has been conducted without any significant co-lateral damage to agriculture or to the environment. This is due to strict adherence to the sound scientifically-based protocols developed by FAO. Dr. Barreto’s team is working closely with governments and researchers to determine where and how to test them further.

A coffee leaf infected with coffee leaf rust (yellow spores), together with an antagonistic parasite of the rust (the white spores), which is attacking the rust. Credit: Robert Barreto

Battling rust on many fronts

Battling coffee leaf rust continues to be a top priority for WCR; the disease is one of the most persistent challenges faced by coffee growers in many parts of the world, and – due to global warming – it is now increasing its range and severity. This is leading to mass migration of disillusioned farmers, notably in Central America. Exploring the potential of biocontrol is part of a multi-pronged effort that also includes: the creation of improved, disease-tolerant coffee varieties; research into the basic functioning of the rust; sequencing the rust genome (in partnership with experts at Purdue University); and identifying farming practices that minimize rust impact.

Harry Evans (left), Robert Barreto (back), Dr. Luis Mejia (right) and local guides in Cameroon. Mission to collect microbial life that helps coffee trees fight against rust.

“The shelf of natural enemies is full… but endangered”

Dr. Barreto says one of the most surprising findings in the project, so far, has been that there are more fungal pathogens attacking the coffee leaf rust than those attacking the coffee plant itself. This indicates that there is a wide diversity of fungi that could be used as tools to control the disease. “The shelf of fungal natural enemies of coffee leaf rust is full of management options,” Dr. Barreto says. “Our surveys in Africa were brief—often just a few days in the forest in each country—so, realistically, there are probably even more novel species that we haven’t discovered yet.” Nevertheless, surveying and studying these fungi in Africa is an urgent task. The last remnants of native forest where wild coffee occurs in Africa, or where it is cultivated in semi-wild conditions, are under great pressure from human activity and are disappearing fast. If coffee becomes extinct in the wild, a wealth of associated microbes – including potential ‘cures’ for coffee leaf rust – may be lost forever.

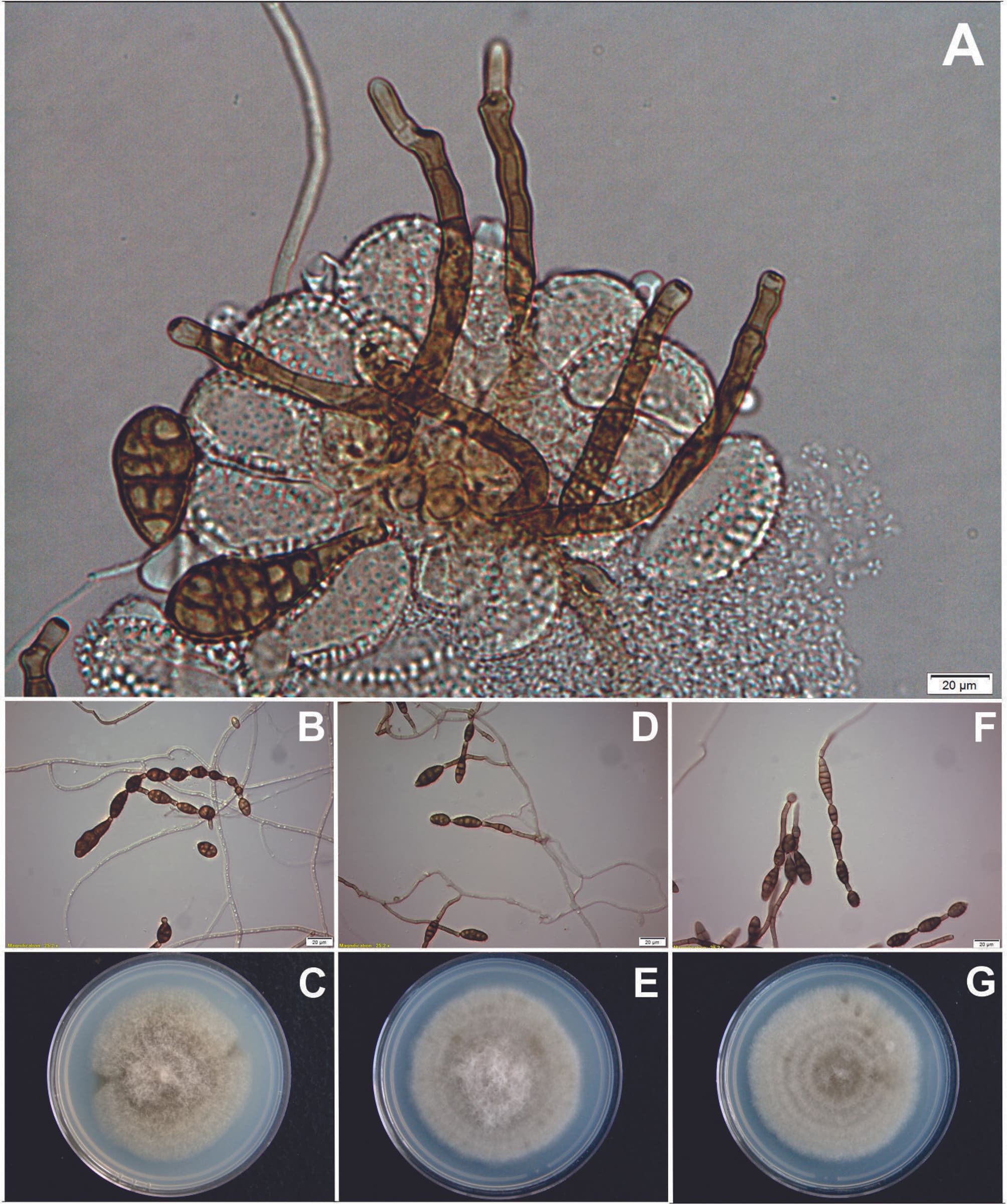

Examples of fungal species belongint to Alternaria which have been found in the study attacking the coffee leaf rust fungus for the first time